The History of Public Medicare

What is Public Medicare?

Public Medicare is the public health care system in Canada which is funded through our taxes. When you see a doctor or visit the hospital for medically necessary services using your OHIP card, you are using Public Medicare. Under Public Medicare, all Canadian residents can receive medically necessary hospital and physician services based on their medical need without user fees or charges. Health care is provided without cost based on our medical need, paid in our taxes, rather than based on our ability to pay or our wealth. Public Medicare enjoys a high level of support from Canadians. It is a source of pride for many, but years of relentless cuts and governments pushing privatization have contributed to problems in Medicare. The solution is not to privatize but to plan well, reorganize care in the public system, and restore and rebuild services that have been cut and downsized too far.

What is it like to not have Medicare?

- Before Public Medicare, Canadians had no choice but to forego medical treatment because they did not have the money to pay for care, leading to suffering and death. Helen Heeney’s book Life Before Medicare tells the story of a young woman with cancer who refused pain medication because it would bankrupt her family. For two months, she had her husband lock her in their home when he left for work so that no one could enter to help her when they heard her screaming in pain. She did not want to bankrupt her family as she was dying.

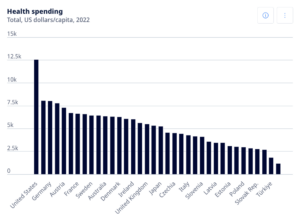

- In the United States where private insurance and for-profit delivery of health care services are widespread, health care costs are almost double per person those in Canada.

- More than 26 million Americans did not have health insurance in 2023 and 38% of residents in the United States delayed getting medical treatment because they could not afford it.

Another Canadian who recounts the dynamic change that Public Medicare brought to the country is Deb Tveit, an Ontario Health Coalition staff member. She was the first of her siblings to be born in a hospital because she was also the first to be born after Public Medicare legislation had been passed. Her family would have needed to pay out-of-pocket for the births of her siblings, so they were all born at home without any support or assistance.

“The only thing more expensive than good health care is no health care.”

Supreme Court Justice Emmett Hall, Chair of the Royal Commission on Health Services

In the United States where private insurance and for-profit delivery of health care services are widespread, health care costs per capita are almost double those in Canada. More than 26 million Americans did not have health insurance in 2023 and 38% of residents in the United States delayed getting medical treatment because they could not afford it. Furthermore, a staggering 100 million Americans are burdened with medical debt. The contrast between the U.S. and Canada highlights the pain and inequities that Public Medicare aims to prevent.

Total health spending in US dollars per capita in 2022 among OECD countries. https://www.oecd.org/en/data/indicators/healt h-spending.html?oecdcontrol-00b22b2429- var3=2022

Total health spending in US dollars per capita in 2022 among OECD countries. https://www.oecd.org/en/data/indicators/healt h-spending.html?oecdcontrol-00b22b2429- var3=2022

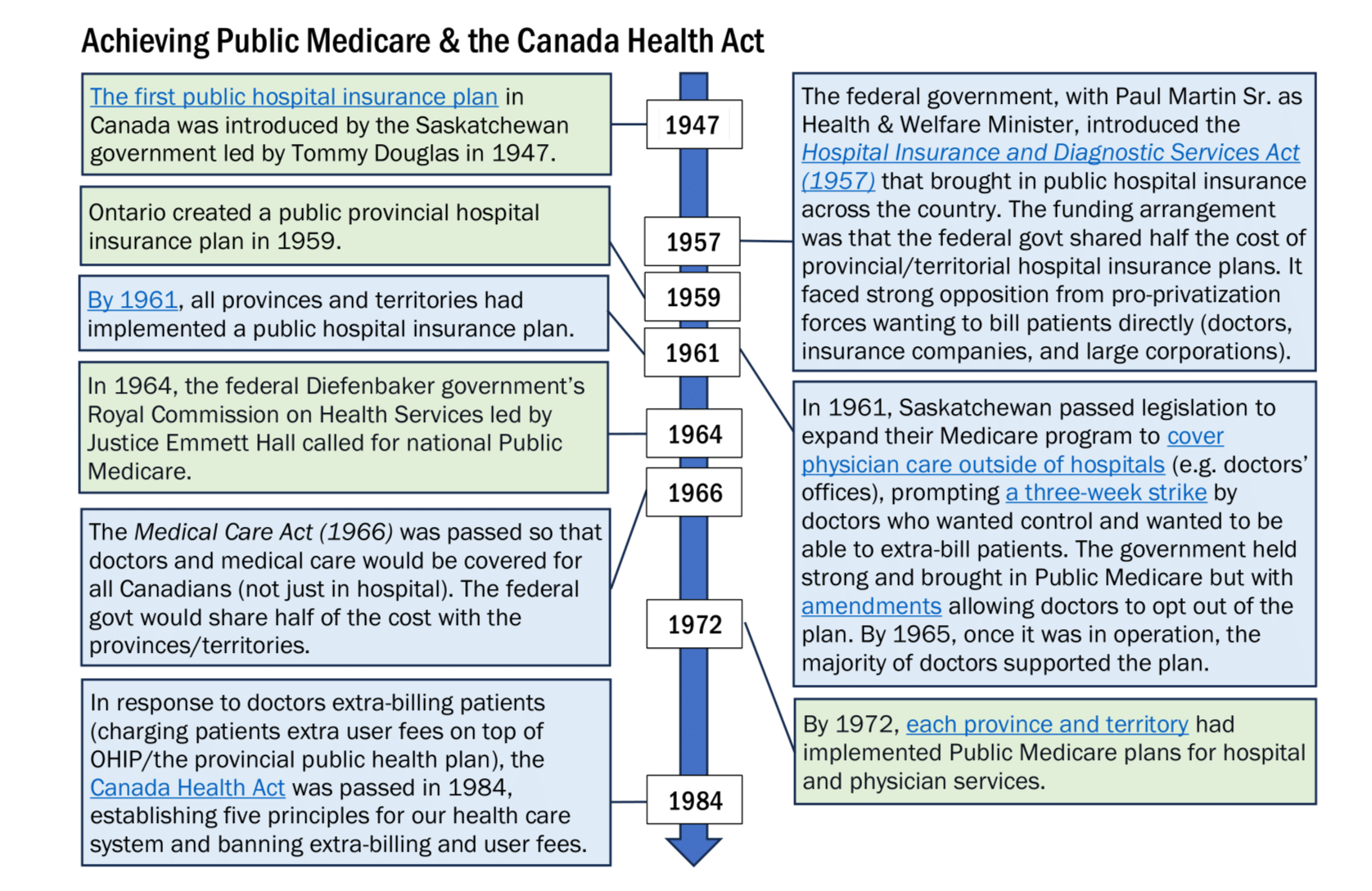

Achieving Public Medicare

Before Medicare, health care was privately delivered and funded, meaning that Canadians paid health care providers for services out-of-pocket or with private insurance. The provinces and territories were mostly responsible for hospital services due to the Constitution Act of 1867 that distributed powers between the federal and provincial/territorial governments.

A public hospital insurance plan in Canada first came into effect in 1947. The Saskatchewan government, led by Tommy Douglas, created a plan that would cover inpatient hospital care for the province’s residents. Doctors overwhelmingly supported it because they could send patients to the hospital without worrying about whether the patient could afford the care. As a result, Medicare in Saskatchewan covered 810,000 people by 1954 and the province had the most hospital beds per person in the country.

The federal government, with Paul Martin Sr. as Minister of National Health and Welfare, introduced the Hospital Insurance and Diagnostic Services Act (1957) that brought in public hospital insurance across the country. The funding arrangement was that the federal government shared half the cost of provincial/territorial hospital insurance plans. It faced strong opposition from pro-privatization forces wanting to bill patients directly, such as doctors, insurance companies, and large corporations. Nevertheless, Ontario created a public hospital insurance plan two years later in 1959 and all the provinces and territories had done the same by 1961.

In 1961, Saskatchewan passed legislation that expanded their Medicare program to cover physician care outside of hospitals, e.g., in doctors’ offices and clinics. The expanded plan would come into effect in 1962. Many doctors and private health insurance companies were against the expansion, and doctors who wanted control and to be able to extra-bill patients went on strike for three weeks. The government held strong and brought in Public Medicare but with amendments allowing doctors to opt out of the plan. By 1965, once it was in operation, the majority of doctors supported the plan.

The federal Diefenbaker government’s Royal Commission on Health Services led by Justice Emmett Hall called for national Public Medicare in 1964. The Medical Care Act was then passed in 1966 so that doctors and medical care would be covered for all Canadians (not just in hospital). The federal government would share half of the cost with the provinces and territories. This evolved into the public health care system we have today. OHIP was formally created in 1971 with The Ontario Health Insurance Organization Act. By 1972, each province and territory had implemented Public Medicare plans for hospital and physician services.

The Canada Health Act

In the late 1970s, the Health Coalitions were formed to safeguard Public Medicare. They participated in the public hearings that led to the creation of the Canada Health Act in 1984.

In response to doctors extra-billing patients (charging patients extra user fees on top of OHIP/the provincial public health plan), the Canada Health Act was unanimously passed, establishing five key principles for public health care (see below). This federal law strengthened existing Public Medicare legislation by ensuring that all Canadian residents could access medically necessary hospital and physician services. Also, the provinces and territories must follow the Act – in other words, stop unlawful extra-billing and user fees – to receive full federal funding.

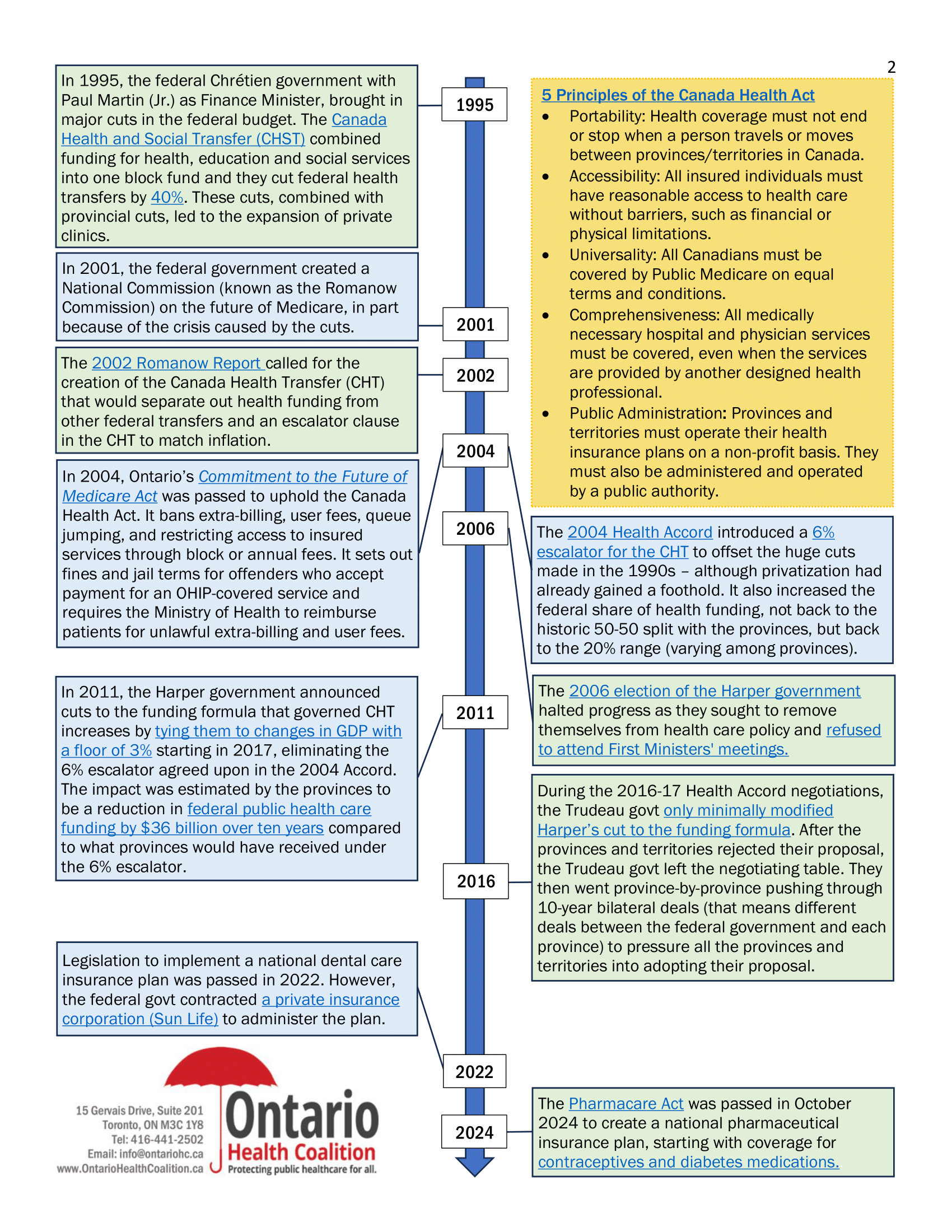

The Five Principles of the Canada Health Act

- Portability: Health insurance coverage must be maintained when a person travels or moves from one province/territory to another within Canada.

- Accessibility: All insured individuals must have reasonable access to health care without barriers such as financial or physical limitations.

- Universality: All Canadians must be covered by Public Medicare on equal terms and conditions.

- Comprehensiveness: All medically necessary hospital and physician services must be covered, even when the services are provided by another designed health professional.

- Public Administration: Provinces and territories must operate their health insurance plans on a non-profit basis. They must also be administered and operated by a public authority.

After the Canada Health Act

Following the Act’s implementation, Paul Martin (the Minister of Finance at the time and son of the previously mentioned Paul Martin Sr.) brought in the 1995 federal budget which was the most regressive in our history. He announced enormous cuts in health funding transfers from the federal to provincial/territorial governments with the Canada Health and Social Transfer (CHST). The CHST combined health, education and social services funding transfers into a single block fund that was smaller than the pre-CHST federal transfer for health care alone. It cut federal health transfers by 40%.

On top of the huge federal cuts, provinces cut funding to their own public hospitals at the same time and private for-profit facilities began cropping up. In particular, pro-privatization governments in Ontario, British Columbia, and Alberta imposed major cuts on their public hospitals. To make matters worse in Ontario, the Harris government implemented tax cuts that favoured the wealthy and corporations.

In 2001, the federal Chrétien government created the Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada (known as the Romanow Commission) to assess Medicare, in part because of the crisis caused by the cuts. The 2002 Romanow Report recommended revisions to the Canada Health Act that would publicly insure more services. It also rejected two-tier health care. In addition, it called for the creation of the Canada Health Transfer (CHT) that would separate out health funding from other federal transfers. It proposed that the CHT have an escalator clause to ensure that the federal share of funding would match economic growth and inflation.

Provincially, Ontario’s McGuinty government passed the Commitment to the Future of Medicare Act (CFMA) in 2004. The CFMA aims to uphold the Canada Health Act by requiring the provincial government to follow it. It bans extra-billing, user fees, queue jumping, and using a block or annual fee to restrict access to insured services. It also sets out fines and jail terms for offenders who accept payment for an OHIP-covered service and requires the Ministry of Health to reimburse patients for unlawful extra-billing and user fees.

Later that year, the 2004 Health Accord marked a beginning of federal re-engagement and re-investment in health care. Its new 6% escalator for the CHT ultimately reversed the huge cuts made in the 1990s – although privatization had already gained a foothold – and increased the federal share of health funding by more than 8%. There was an opportunity to build on the 2004 Accord, especially through a proposed national pharmaceutical insurance plan, but the 2006 election of the Harper government halted progress as they sought to remove themselves from health care policy and refused to attend First Ministers’ meetings.

Reductions and Expansions

In 2011, the Harper government announced cuts to the funding formula that governed Canada Health Transfer increases by tying them to changes in GDP with a floor of 3% starting in 2017, eliminating the 6% escalator agreed upon in the 2004 Accord. The impact was estimated by the provinces to be a reduction in federal public health care funding by $36 billion over ten years compared to what provinces would have received under the 6% escalator.

During the 2016-17 Health Accord negotiations, the Trudeau government proposed only minimal changes to Harper’s cut to the funding formula. After the provinces rejected the proposal because it was insufficient, the Trudeau government left the negotiating table with all the provinces and instead went province-by-province pushing through 10-year bilateral deals (different deals between the federal government and each province) to pressure all the provinces and territories into adopting the proposal. They continued to reduce the share of federal health funding and tie health funding to economic growth instead Canadians’ needs.

After the 2021 federal election, the NDP and Liberal parties formed a confidence and supply agreement in which the NDP required the creation of national public health plans for dental care and prescription drugs. Legislation establishing the Canadian Dental Care Plan was passed in 2022. While the plan is a step forward in improving access to dental care, a private insurance corporation (Sun Life) has been contracted to administer the plan.

The Pharmacare Act was passed in October 2024 to create a national pharmaceutical insurance plan starting with coverage for contraceptives and diabetes medications. However, each province and territory must make individual agreements about the terms of plan with the federal government. This will significantly impact pharmaceutical access in each jurisdiction with Alberta and Quebec already looking to opt out of the plan.

News

Reintroduction of NDP Bill to protect health care workers from reprisals for speaking out against workplace violence needed now more than ever: CUPE

OTTAWA, ON – A poll of more than 1000 registered practical nurses found that more than 60% are considering leaving. At a media conference in front...

67% of Guelph hospital nurses, PSWs other staff physically assaulted at work as pandemic violence surges; new CUPE poll finds

GUELPH, ON – Guelph General Hospital registered practical nurses (RPNs), personal support workers (PSWs), cleaners, porters and clerical staff...

Thousands of Thunder Bay, Kenora, Sault nurses, PSWs, other staff subject to violence at work during pandemic; CUPE and Unifor say

NORTHERN ONTARIO – From hurled racial slurs to an oxygen tank projectile, pandemic tensions are subjecting hospital staff throughout northern...